There are several components to every good spec chart. First is the POMs or points of measure, second is the graded spec measurements, and third is the tolerances. The tolerances control what variance from the spec measurement is acceptable. Writing proper tolerances is a balance between controlling product quality and having realistic expectations for a production environment. Each POM gets its own tolerance, so how do you get that balance right for each one? These are the factors to consider when writing POM tolerances.

How to read POM tolerances

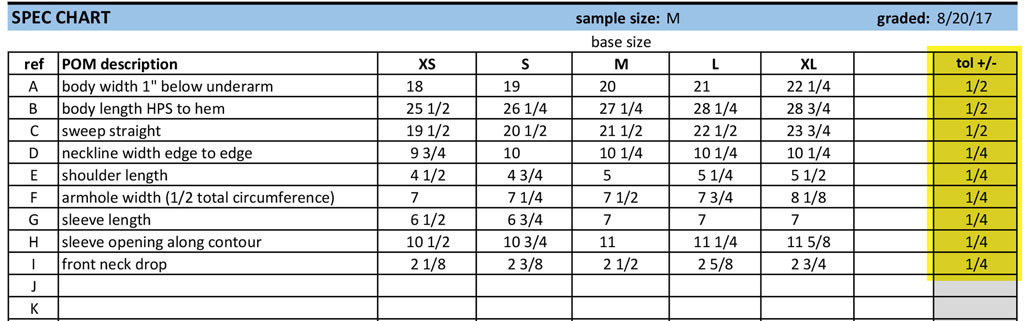

POM tolerances are usually written as a number – often a fraction – with a plus/minus sign. The tolerance is the variance from the spec measurement for that POM that is acceptable. For example, if the across bust measurement is 20” and the tolerance is plus or minus ½”, that means garments measuring between 19 ½” and 20 ½” meet the spec. Each point of measure has its own tolerance.

Read on to learn how to determine appropriate tolerances for each of the points of measure on your garment.

Garment sizing

Tolerances are not only for quality control standards, but they also aid in separating your sizes from each other. If you have a sample that is missing a size label, you should be able to use your spec chart POMs and tolerances to determine what size it is.

For the key circumference measurements like bust, waist, and hip, you want your tolerances to be small enough that your sizes don’t overlap. If the total tolerated variance is bigger than the grade rule for that POM, you might end up having a larger-sized garment that is actually smaller than the size below it or vice versa. For example, you might end up with a size XL that still meets the spec tolerance, but measures smaller than a size L. This can be confusing for your team and to your customers.

The first step to keeping these measurements from overlapping is to identify how the garment is sized. Numeric sizing (6, 8, 10, 12, etc.) has a smaller grade rule than alpha sizing (S, M, L, etc.) which means that you’ll want to use smaller tolerances as well. Subtract the measurement for one size from the size above it, then divide that number by two. Try to keep your tolerance for that POM at or below that amount.

Importance of garment measurement

Another factor to consider in writing POM tolerances is the importance of that POM to the fit and integrity of the design. More important POMs get smaller tolerances.

How do you know if the POM is important? If the measurement was significantly off, how noticeable would it be? For example, 1” bigger than spec along the sweep of a ballgown circle skirt would probably not even be noticeable, but 1” bigger across the shoulder of a fitted blouse would completely throw off the fit.

POMs that are critical to the fit get smaller tolerances so that those areas are more tightly controlled. POMs I’d put in this category are across shoulder, across bust/waist/hip (if the style is fitted), bicep width, and neck width and drop.

Size of measurement

The size of the measurement for each POM has an effect on the tolerance amount as well. Again, the tolerances are there to keep the garment measurements in line with the proper fit and intended design for each size. The smaller the detail, the more noticeable any variance in measurement will be.

Smaller details with smaller measurements need smaller tolerances. For example, the tolerance on the sweep of a full skirt might be 1”, while the tolerance on the width of a welt pocket opening might be ¼”, and tolerance on the width of a neck binding might only be ?”. There is no direct ratio as to the measurement amount and the tolerance amount, but in general, the smaller the measurement, the smaller the tolerance.

So how small can your tolerances get? There are a lot of moving parts in garment production and each one will have some margin of error. Changes in the fabric, cutting, and sewing will all add up to some variance from the original spec measurement. Knowing this, your tolerance can’t feasibly be too small. I almost never use a tolerance of less than ?” and I reserve that small of a tolerance for important, small POMs. Somewhere between ¼”-½” is more common and up to 1” is appropriate at times.

Type of garment and fabric

Like the type of sizing, the type of garment and the type of fabric can influence the tolerances you write for each POM. More relaxed, loose garments don’t need as tight of tolerances as more tailored, fitted ones. This is due to a combination of the other factors we talked about above, but garment type is another way to look at this. Relaxed, casual garments are typically alpha sized and there would have to be greater variance from the spec before the fit is noticeably different.

Fabric plays a role here as well. Wovens carry more structure and can meet smaller tolerances. Knits have more bounce, stretch, and give which makes meeting a tight tolerance more challenging. Not only do knits often shrink and move during cutting and sewing, but the finished garments do too. This makes it more difficult to get a precise measurement to check it against the spec. Because of this, tolerances for knit garments are more generous in many cases. Especially in length, knit tolerances tend to be bigger because knits shrink more in length than in width.

Knowing how to write appropriate POM tolerances will help you keep control of your sample and production quality and help your factory meet those standards. The garment’s sizing, category, and fabric as well as the POM location and size all impact what that tolerance should be.

P.S. If spec charts and writing tolerances for your POMs is still confusing, ask your patternmaker! They will be able to help you determine the optimal tolerance amount for each POM. I include graded spec charts with tolerances in all my service packages.