This is the second post in a 3-part series. If you missed the first post where we talked about what you are making, you can read it here.

So you know what you want to make and what qualities you want in the fabric, but how do you describe what you are looking for? Most suppliers don’t have swatches of every fabric they offer available for you to look at and feel, so it is important to know how to communicate your fabric needs with the proper terminology.

There are two main elements to describing fabrics. The first is by what fiber it contains, and the second is how it is constructed. Think about it like ingredients and cooking method. The fibers are the raw ingredients that go into the fabric. After ingredients are gathered and prepped, they can be cooked multiple ways either on their own or combined in different ratios to create a dish. The same is true for fabrics. Fibers can be combined into finished fabric using a variety of construction methods. Both the fiber type and the construction lend fabrics their qualities and behaviors.

Describing fabrics by their fiber

Fibers fall into two broad categories – natural and man-made. Natural fibers include plant-based fibers such as linen, hemp, cotton, and bamboo. Natural fibers also include animal-based fibers such as silk and wools like merino, cashmere, and angora. Man-made fibers are fibers like rayon, modal, and acetate as well as plastic-based synthetic fibers like polyester, nylon, acrylic, and vinyl.

What fiber you choose for your design will depend on what qualities you are looking for and what is in your price range. Generally, natural fiber fabrics cost more than synthetic ones, but they are often more breathable and are considered more desirable. Know what qualities are important to your customer or production process before sourcing fabrics so it will be easier to make decisions on a fiber that is right for your design.

Describing fabrics by their construction

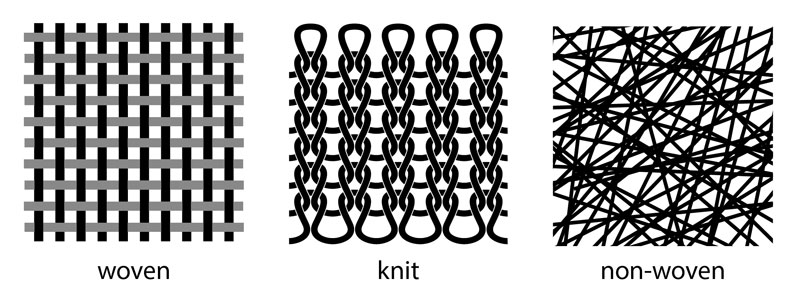

The next piece in describing fabric is its construction. There are three main types of fabric construction – woven, knit, and non-woven.

Woven fabrics are made using threads going lengthwise – called warp – and threads weaving back and forth crossways – called weft. Wovens usually don’t stretch in either width or lengthwise directions, though sometimes stretch fibers like elastane or spandex are mixed in to create some stretch. They do have beautiful drape and “stretch” when cut on the bias (at a 45 degree angle to the edge). A 1930s slip dress is a great example of woven fabric on the bias.

Below are a few examples of woven constructions and some of their typical apparel applications.

- Plain weaves are used in many popular fabrics including quilting cotton, muslin, tweed, and chambray. Depending on the thickness of the threads used and how tightly they are woven, plain weave fabric can have many purposes. Common in clothing, it is used on blouses, shirts, trousers, outerwear, and many other items.

- Twill has a diagonal structure. Twill weaves are used often on pants and jackets. Denim is a type of twill weave fabric that uses a colored warp and white weft.

- Satin weaves create a sheen on the surface of the fabric by having the warp skip or float over several weft threads. Satin is often used for special occasion, bridal, sleepwear, and lingerie.

- Jacquard weaves are complex weaves that create intricate patterns of many colors. Created on special looms, these fabrics are used in clothing on lined formalwear and jackets.

Knits are created by looping yarns in a chain structure either lengthwise or widthwise. They stretch widthwise, with some types of knits stretching in the length direction as well. Knit fabrics are a common staple in our wardrobes.

- Jersey knits are the fabric that is found in your typical tee-shirt. There is a face side with tiny columns of “v” running lengthwise with a reverse side that looks like rows of squiggles running across the width. Jersey knits stretch more in the width direction than they do in length.

- Rib knits are found on collars of tee-shirts, cuffs and hems of hoodies, as well as sometimes the main fabric of the garment. Rib knit fabrics look similar on both sides of the fabric and they have an accordion-like look with vertical ribs that give the fabric its name.

- French Terry fabrics look like jersey on the face side, but have a loose, towel-like texture on the reverse side. You can find French terry in garments like sweatshirts and beach cover-ups.

- Tricot fabrics are sturdy knits that stretch in all four directions. They don’t have an obvious face, but the face has fine vertical ribs and the reverse side has fine horizontal ribs. Tricot knits are often found in swimwear, lingerie, activewear, and as linings for knit garments as they work great for form-fitting and flexible garments.

Non-wovens don’t have a defined grain like knits and wovens do and are constructed by bonding loose fibers together instead of knitting or weaving yarns. Felt is a common non-woven fabric we probably all remember from grade school craft time. In apparel, felts can be used for coats and other lofty garments. Batting and interfacing are also non-woven fabrics used in apparel.

Fabric descriptions follow this fiber and construction description format. For example, you might see fabrics listed as polyester/spandex jersey, silk satin, or cotton/spandex twill denim.

Describing fabrics by their weight

Fabric descriptions often include the fabric weight. This is listed as ounces per square yard (oz/yd) or grams per square meter (GSM). Weight does not always equate to the fabric’s opacity, though. A fabric can be very heavy, but still see-through. I find weight descriptions to be most useful when combined with other descriptors or for comparing two fabrics of the same fiber content and construction.

Describing fabrics by their finishes

In addition to the fiber and construction, fabrics can also have added finishes that enhance the performance or aesthetic qualities of the fabric. These finishes include dying, printing, washing, and performance treatments.

- Dying and printing are finishes that add to the visual look of the fabric. Dying will change the color on both the front and back sides of the fabric while printing is usually applied to the face side – leaving the reverse side blank. Note that different printing and dyeing methods will have varied results with different fibers – with some fibers taking the color better than others. If you intend to print or dye your fabrics, make sure to consult your printer and fabric supplier before purchasing to make sure your fabric will work for your intended technique.

- Washing can either be done at the bulk fabric stage, or at the garment stage and can change the fabric color and feel. Denim garments are often given wash and distressing treatments to give them their worn-in look.

- Fabric surfaces can also receive treatments that simply change their hand feel. Brushed fabrics fall into this category and have a soft, combed face that is slightly fuzzy or peachy feeling.

- Performance treatments are common in athletic apparel to give them qualities such as moisture-wicking, anti-microbial, fast-drying, water-repellant, flame retardant, and UV protection. These finishes are accomplished through the addition of treated yarns or special fibers in the construction or by chemical or natural additives on the finished fabric.

Describing fabrics by their end use

Another, less technical, way you can describe fabrics is by their use. Not all fabrics are suitable for every type of garment. For example, a blouse can be fairly light and sheer, but pants typically are made of slightly heavier fabric with denser construction.

When searching for the right fabric, you can ask to see fabrics for your particular end garment use. Dress weight, bottom weight (pants and skirts), and blouse weight are common terms used to describe categories of suitable fabrics. You can even get more specific about the end use and ask for shirting, coating, suiting, or swimwear fabric, etc. Because fabrics are categorized this way, if a fabric supplier asks you what you intend to make with the fabric, they aren’t trying to be nosy or steal your design ideas, they are simply trying to help you find fabrics suitable for your specific product.

Now that you know the qualities you are looking for and how to describe your fabric with the fiber content, construction, weight, and finishes, the next step will be to go out and find it! The next post in this series will cover where (and where not) to start looking, what to do when your sample fabrics arrive, and the key information you need to be asking and tracking during the sourcing process.

Tyler Johnson

11:20 am July 17, 2019That's a good idea to make sure that you keep in mind what the clothing will be used for when choosing fabric and weave. I would think that it would be a good way to make sure that it works as intended. I would think that it would be good to have stretchy sports clothing be made out of different material than a work shirt would. https://www.spandexhouse.com/cotton-lycrareg/